Brussels is recalibrating its economic compass, and the repercussions are rippling across Europe. While Switzerland has largely overlooked this shift, the European Union’s burgeoning focus on Local Content Rules (LCRs) signals a profound transformation in investment incentives, directly impacting its internal market. Swiss diplomacy and businesses must now actively engage with this evolving landscape.

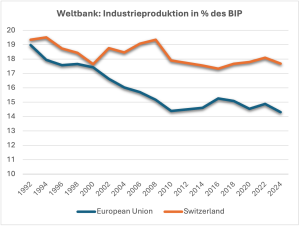

The EU is undergoing a significant rearmament, not solely in military terms, but economically. Experts are referring to this as a “geoeconomic revolution.” Supply chains are under scrutiny, investments into and out of the EU are being controlled, and heavily subsidized imports face the prospect of punitive tariffs. The underlying objective is clear: to reindustrialize EU member states. A leaked legislative draft from the European Commission determines that by 2030, at least 20 percent of the EU’s GDP will originate from internal production. A notable increase from approximately 14 percent in 2024.

Figure 1: World Bank Data

A critical, yet largely unheeded, aspect of this shift in Switzerland is the rise of Local Content Rules (LCRs). These regulations, gaining traction within the EU, mandate that companies sourcing products must procure a specific proportion of materials, labor, or services from within the EU. The Commission’s rationale is multifaceted: the EU acknowledges its inability to compete with the extensive subsidies offered by China or the United States. Furthermore, many major economies already systematically implement LCRs. By introducing its own LCRs, the EU aims to bolster investments, particularly in green technologies, within its internal market.

Several legislative proposals from the EU Commission are designed to operationalize these intentions:

- The recently leaked “Industrial Accelerator Act“ proposes a minimum share of EU-produced goods for public procurement and state funding programs, specifically targeting green steel and the automotive industry. Additionally, it would prohibit foreign investors from owning more than 49 percent of an EU company operating in critical sectors such as battery manufacturing or the automotive industry. This package is currently under negotiation, with its publication anticipated by the end of February 2026. Whether Switzerland will be affected remains to be seen. The draft includes provisions that could exempt third countries with open public procurement systems from these requirements. It is presently unclear whether the existing bilateral agreement between the EU and Switzerland on public procurement meets these stipulations.

- The EU Automotive Package mandates a 90 percent reduction in vehicle CO2 emissions by 2035. The remaining ten percent can only be offset by EU low-emission steel or EU biofuels. Furthermore, a potential obligation for large companies to further decarbonize their vehicle fleets and prioritize EU-produced vehicles is under consideration. This package is currently being debated by the European Parliament and member states. It also includes measures to foster a battery supply chain (for EVs) within the EU, backed by €1.6 billion. Complementary “supercredits” are envisioned to specifically support small and affordable “Made in EU” EVs.

- The Net-Zero Industry Act specifically supports the production of climate-neutral technologies within the EU. It stipulates that supply chains must not source more than 50 percent from any single third country. In public tenders, EU technologies will receive preferential treatment. By 2030, at least 40 percent of the EU’s annual demand for green technology is expected to be met by EU production. This legislation is already in force and could pose significant challenges for Swiss industry.

- Other notable initiatives include the Critical Medicines Act (aiming for more EU-produced medicines) and the Critical Raw Material Act (promoting increased processing of rare earths within the EU).

This is merely the beginning.

The precise definition of “Made in EU” in the future remains ambiguous, as the annexes defining these requirements for the various laws are yet to be finalized. Moreover, some member states have not yet implemented the definitional guidelines. However, the fundamental principle is straightforward: where EU or member state funds are disbursed, the EU itself should benefit.

Behind closed doors in Brussels, intense negotiations are underway regarding the implementation of these measures. The extent to which the final framework will be compliant with WTO rules is still uncertain. Stéphane Séjourné (FR), the influential Commission Vice-President for Prosperity and Industrial Strategy, is advocating for particularly restrictive rules. Such regulations could effectively bar Swiss suppliers, for instance, from accessing European public procurement contracts.

These public contracts represent a significant economic lever, accounting for 14 to 16 percent of the EU’s GDP, approximately €1.9 to €2.5 trillion. State funding programs are not even included in this figure. Germany, for example, is launching a €3 billion funding program for EVs, which currently still includes Chinese car manufacturers.

If strategic sectors like batteries, cleantech, or semiconductors, which attract substantial private investment, are further integrated, a rough estimate suggests that 40 to 50 percent of EU production could be affected by LCRs. While Switzerland may not be the primary target, it could nonetheless face exclusion. The Swiss mechanical and electrical engineering industry, for instance, directs approximately 60 percent of its exports to the EU, supporting 300,000 domestic jobs.

Strict LCRs in the EU would likely have severe repercussions for Switzerland’s economic standing. This issue is absent from the new package between Switzerland and the EU.

A noteworthy conclusion from the 2024 SECO study on the impact of industrial policy on Switzerland is that the anticipated welfare loss due to international industrial policy measures is merely 0.06 percent of Swiss GDP. Most Swiss companies, according to the study, remain optimistic. However, the study’s authors assume that the EU will introduce few LCRs and that Swiss products will retain access to the EU internal market (page 19). In light of current developments, these assumptions now appear questionable.

A cautionary case in point for Switzerland is the EU’s imposition of safeguard measures in November 2025, including import restrictions and tariffs on ferroalloys, which are crucial for steel production. Norway and Iceland, both EEA members, were affected, demonstrating that the EU’s geo-economic revolution spares even allied nations.